A communist cult brings a lot to the table

How a polyamorous cult that pioneered eugenics ended up at my Thanksgiving dinner.

Every year, my family gathers at my grandparents’ house for our Thanksgiving meal. When my sister and I were younger, we used to spend the night and help prep for the next day. My sister and grandma handle the side dishes and desserts, while my Grandpa and I work together on the stuffing and turkey.

This year was a little different: my Grandpa spent Thanksgiving in an inpatient rehabilitation facility, recovering from surgery (he fell about a month ago).

My grandpa had been preparing me for this over the last few years, so I mostly knew how to make the stuffing. Family recipes are a little difficult because nothing is written. So, when I asked him how much sage and thyme to add, the answer was vague.

I ended up following my sense of smell, relying on my memory of past years for comparison. So when we all sit at the table to eat dinner, one person short, I’m eager to try the stuffing and see how it turned out.

My grandma has the silverware wrapped in a thick cloth napkin, and as I unwrap it my fork is upside down. I see a name stamped onto the back, and hold it up to read it.

“Oneida Community Stainless”

I turn to my dad to point it out to him, since I’ve told him this story before. The rest of my family doesn’t really know what’s going on, so I try to get them up to speed.

That name probably doesn’t ring a bell to most people, but Oneida is one of the largest flatware brands in the world. It’s a little hard to miss once you start looking — you’ll see it in supermarkets, at restaurants, and maybe at your grandma’s dinner table.

That’s not why I was familiar with it, though. Oneida stuck with me because of the company’s strange origin story, which I learned about on an episode of Avery Trufelman’s “Nice Try” podcast. Here’s my retelling of that story.

Oneida, New York: Heaven on Earth

The Oneida Community was founded in 1848 by John Humphrey Noyes, a young seminary student who was swiftly expelled from religious circles after he declared he had freed himself from sin and achieved full salvation.

Noyes found himself enlightened and divinely positioned to spread those beliefs, and established enough of a following to found a community of Perfectionists. Noyes and his followers believed Christ had already returned in 70 A.D., and that they were able to rid themselves of sin and create Heaven on Earth. Noyes called it “Bible communism.”

The group was founded in Putney, Vermont, and faced early persecution for their beliefs. Noyes went on the run from adultery charges, which were threatened by authorities for the community’s belief in “complex marriage.”

Noyes believed the members were all a part of one family, rejecting the idea that men held ownership over their wives or that relationships were exclusive. The members were able to have relations with the opposite sex freely, as long as it was consensual and the potential for childbirth was avoided (you can read between the lines here). If two members became too attached to one another, they were separated.

Because the community’s members were not supposed to procreate, birth rates stayed low and unintentional pregnancies were rare. Noyes controlled the creation of children by pairing members based on intellectual and spiritual qualities. He believed those traits were hereditary, and that choosing parents based on their intellectual merit would produce children with those same traits.

That means the Oneida community was the first to practice a form of eugenics (that word didn’t even exist yet at the time) that they called “stirpiculture.” The community’s children (“stirpicults”) were raised in a group home away from their parents, and the responsibilities of caring for them was shared by the community.

Noyes also had the older men and women in the community act as sexual mentors to the adolescents, a practice that he had oversight of and encouraged members to engage in. Intellectually, the community valued education and literacy for both children and adults. They provided schools for the children, published periodicals and pamphlets, read books aloud to members as they worked, and eventually allowed the children to attend universities.

Like most cults, the group began to fizzle out after the new generation came of age. The group experienced pressure, legal and otherwise, from neighbors who weren’t fond of their lifestyle, and were left without a clear leader after Noyes’s son didn’t follow his father’s footsteps. In 1881, the group dissolved into a corporation, preserving the community’s manufacturing businesses.

The Silver Lining (or plating, rather)

If I was to rate some of the contributions of the Oneida Community, it’s sort of a mixed bag that’s mostly bad. To quote Wikipedia (you can take the sighs elsewhere), the community “embodied one of the most radical and institutional efforts to change women's roles and improve female status in 19th-century America.” While women were not equal in every respect, the community’s ideas were absolutely outside the bounds of society.

They also set into motion a radical experiment in creating a utopian society through communism, led by Noyes’s interpretation of the Bible and his beliefs about Heaven. Noyes’s dedication to using Heaven as the ultimate model for utopia is, at the very least, an interesting thing to think about.

However, they were also pioneers of eugenics, groomed adolescents to become devoted members through inappropriate sexual experiences, and was a cult that focused on insulating their members from outside ideas. That’s worth saying.

Those are some strong legacies to compete with, but its enduring legacy is actually the goods their members began manufacturing.

In the community’s early years, they kept themselves afloat by growing their own fruits and vegetables. However, they began dipping their toes into manufacturing, pulling together their talents and innovations to create profitable businesses selling steel chains, sewing thread, embroidery silk, and silver-plated tableware.

The success of their industry quickly outgrew the labor capacity of the community, and they began hiring outside workers to assist in the production. They paid the employees very high wages, and also rewarded them through profit-sharing plans that “often amounted to fifty cents on every net dollar earned by the company.”1

So when the community dissolved in 1881, they didn’t just vanish into thin air. They actually turned into a joint-stock company: Oneida Community Ltd.

Here’s an excerpt from Syracuse University history professor Nelson Blake’s foreword to the library’s collection on the community:

Usually prosperous, the corporation showed characteristics unique for its day in paying higher than prevailing wages and in otherwise benefiting its employees through planned housing and the encouragement of schools. Much of the old idealism thus found a new expression in the field of welfare capitalism.

The company’s management, led by Noyes’s son Pierrepont, began to focus on bringing their tableware to the national market as their other industries became less profitable. Pierrepont was not interested in spreading his father’s beliefs, but was undoubtedly influenced by his childhood in the community. Under his leadership, Oneida Limited rose to prominence as the country’s leading tableware manufacturer.

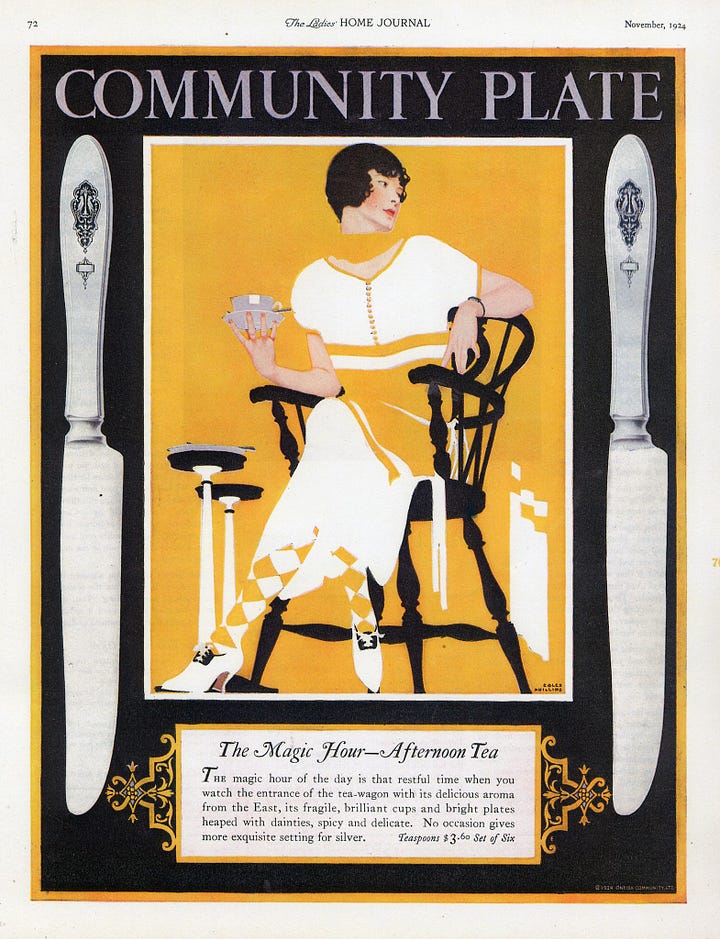

The company grew their market share primarily through advertising campaigns in American magazines. The advertisements usually featured illustrations by renowned American and European artists, which placed their tableware next to images of luxury products. They advertised in bridal, lifestyle, and fashion magazines, appealing to middle-class white women who aspired to the lifestyles promoted by the publications.

In their 1940 “Community Inspires” campaign, the company commissioned the couture houses of Lucien Lelong, Schiaparelli, Molyneux, and Balenciaga to design garments inspired by their tableware.2 The campaign landed them spots in Vogue that were not normally afforded to middle-market brands like theirs, and connected the brand to names that were idolized among “cultured” Americans.

Their advertising efforts were successful, and by the 1980s, the company manufactured at least half of all flatware in the United States. Their constant presence in magazines, which were experiencing enormous cultural influence, allowed them to tap into American’s luxury aspirations with a price point that was within reach.

However, the company began to struggle as the 21st century approached. In 2006, the company filed for bankruptcy after it couldn’t recover from the economic downturn caused by 9/11. It no longer manufactures its products in the United States, and ownership has been passed between hedge funds and holding companies. It is currently owned by Lenox, one of the brand’s former competitors.

Today, Oneida barely exists as a company. However, through all those acquisitions, mergers, and dissolutions, Oneida’s selling power as a brand has survived. When I was looking for my own silverware for my apartment, it kept coming up everywhere I looked.

And now, I leave you with the same burden. Every time you see the Oneida name, all you’ll be able to think of is the crazy story that put that fork on the Thanksgiving table.

Thank you for indulging me as I told this one. I’ve been working on it for a while now, and between Thanksgiving and catching a cold it isn’t as timely was I would have liked. I spent way too much time for it to end up in the garbage pile though.

A special thanks to Avery Trufelman for the episode in which I first learned about Oneida. I’ve admired her for a long time, and truly believe she is one of the most talented researchers/storytellers/podcasters in the world. Everything she touches is gold, and one day I want to tell stories that are as unique as hers.

She does a way better job at explaining the group’s quirks and history than I did. I suggest you give it a listen if this interests you in the slightest.